Milwaukee Open Housing Marches: 50th Anniversary

Counter-protestors driven by fear, hatred, white residents recall

By Dean Bibens

Editor’s note: This is one in a series of 15 pieces about the Milwaukee Open Housing marches, which took place 50 years ago beginning on Aug. 28, 1967. Watch for the stories every Monday and Thursday through the end of July. This article is republished with permission from “Marching On: 50 Years After the Milwaukee Marches,” a project of a journalism capstone class at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication.

Gus Ricca recalls 1967 as a frightening time for everyone in Milwaukee, not just for African-Americans who faced down white protesters as they marched for open housing.

Now 72, Ricca graduated from Hurley High School in 1963 and moved to Milwaukee in 1964 looking for a job, just a few years before the marches began. He was living on 24th Street and Kilbourn Avenue, near the Eagles Club, an all-white fraternal organization complete with workout areas and a dance hall. The club was a frequent counter-protest location and a haven for many racist bigots, Ricca said.

“I saw demonstrations take place at the Eagles Club and, to be quite frank, it was frightening,” said Ricca, a former factory worker at Falk Corp., 3001 W. Canal St.

“I didn’t join in on the counter-protests,” he added, “because I hadn’t really chosen a side in the issue. But looking back on it, sitting out of it was just as bad as being a part of the (counter) demonstrations.”

Many white residents felt as though they were trapped, Ricca said, because if they spoke up for African-Americans, they would be shunned in their communities.

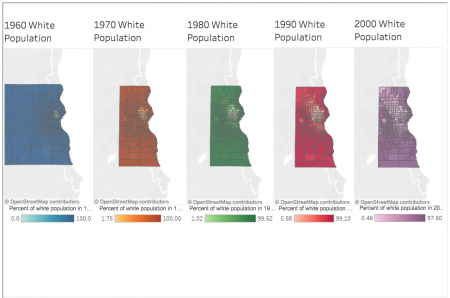

Graphic by Jack Goods. Republished with permission from “Marching On: 50 Years After the Milwaukee Marches,” a project of Professor Herbert Lowe’s journalism capstone class at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication. Click on the graphic for more details.

Ricca said many were also fearful because African-Americans were standing up to racism and whites were not ready for change.

“Malcolm X was a leader that I read about a lot, and I think he definitely put the fear of God into a lot of people,” he said of the civil rights leader, who was slain in New York in 1965. “You knew that he wasn’t going to back down, and neither were the African-American people; they had a real reason to fight.”

Ricca added that “whites were fearful that they would fall into the minority,” and that “people in general don’t like change, in my opinion, because it almost makes them feel like they can be at a disadvantage.”

At the time, Ricca’s friend Kenneth Germanson lived in an all-white area on the city’s South Side, just north of General Mitchell International Airport. Germanson, now 88, witnessed the resistance as a Milwaukee Sentinel reporter.

Nazis march along 16th St. at Forest Home on Sept. 23, 1967. (Photo courtesy of Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and Milwaukee Public Library)

Germanson, who has lived in the Town of Lake for 53 years, remembers once arriving at his house and being greeted with a racist remark by a neighbor: “Welcome to our neighborhood – the last bastion of whites.”

In that moment, Germanson said, he took “the coward’s way out” and didn’t stand up to him. Today, he points out, there are signs around the community that say, “All people are welcome, regardless of where they came from.”

Even so, he believes that racism still exists in Milwaukee, mostly because “people don’t have the courage to stand up for each other.”

Ricca offered another reason why discrimination still exists.

“I know a lot of my friends’ parents were military families and they had different beliefs than others,” he said. “Racist sentiments have been passed down to families for years — and it’s just not right.”

“There was an open wound in the sense that the African-American community felt left out 50 years ago,” Marcoux said, “and today, most of the poverty that we have seen over the years is driven by that very racial divide.”

The commissioner added: “The racial issues are real in this city, and it’s evident in where the white population has gone since the housing marches. Many have fled to suburban areas in Milwaukee County and beyond.”

Germanson said “a majority of the whites” who lived on the South Side 50 years ago moved to the suburbs to “get away from it all.”

Whatever their reasons, Germanson said, “they were magnified by the hatred.” Looking back on it now, he added, “I don’t think anything justified the hatred that was shown.”

Open housing marches placed spotlight on racial discrimination, segregation

Open housing marches placed spotlight on racial discrimination, segregation

High school sweethearts recall open housing struggle

High school sweethearts recall open housing struggle

Counter-protestors driven by fear, hatred, white residents recall

Counter-protestors driven by fear, hatred, white residents recall

Former St. Boniface student says Father Groppi ‘taught me how to love’

Former St. Boniface student says Father Groppi ‘taught me how to love’

Fifty years after open housing marches, residential segregation still norm in Milwaukee

Fifty years after open housing marches, residential segregation still norm in Milwaukee

Rozga shares legacy of open housing marches through play, poems

Rozga shares legacy of open housing marches through play, poems

Housing discrimination personal issue for Open Housing marcher’s family

Housing discrimination personal issue for Open Housing marcher’s family

Anger motivated marcher to participate in open housing demonstrations

Anger motivated marcher to participate in open housing demonstrations

‘We fought just as hard’: Women in the March on Milwaukee

‘We fought just as hard’: Women in the March on Milwaukee

Open housing marches a family affair for former Youth Council member

Open housing marches a family affair for former Youth Council member

Open housing marcher says ‘state of the city has gotten worse’

Open housing marcher says ‘state of the city has gotten worse’

Marcher sees link between open housing marches, Sherman Park unrest

Marcher sees link between open housing marches, Sherman Park unrest

Fight for equality must be rooted in community, sustainability, leaders say

Fight for equality must be rooted in community, sustainability, leaders say

Council is more diverse than in 1967, but city faces similar problems

Council is more diverse than in 1967, but city faces similar problems

Open housing marcher passes legacy of activism to daughter Chantia Lewis

Open housing marcher passes legacy of activism to daughter Chantia Lewis